Eritrea’s arbitrary regime downplayed

Refugee protection denied

(10.03.2020) In July 2018 a peace treaty between Ethiopia and Eritrea was concluded, formally ending the border war between the two countries (1998-2000). This was followed in November 2018 by the lifting of UN sanctions against Eritrea. Since then, there have been repeated voices stating that the Eritrean regime has no more excuses to continue the repressive militarization of the population. Furthermore, the peace brought the hope that the human rights situation in the country would improve. However, as can be seen from the reports of Amnesty International1, the UN Human Rights Committee2, the UN Special Representative on the human rights situation in Eritrea3 and most recently Human Rights Watch4, this is not the case.

Significantly decreasing protection rates in asylum procedures

Nevertheless: Fewer and fewer asylum seekers from Eritrea receive refugee recognition in Germany. In 2015 the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF [Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge]) still recognized 95.5% of Eritrean asylum seekers as refugees.5 In the following years this rate of protection has fallen massively. Increasingly, Eritreans are only granted subsidiary protection, which goes hand in hand with a much less favourable legal status. The number of persons who simply receive a so-called “prohibition on deportation” (Abschiebungsverbot) or even a refusal of permit altogether has also increased considerably. In 2018, a reduced number of 39.5% of Eritreans received refugee protection, and 49.7% received subsidiary protection.6

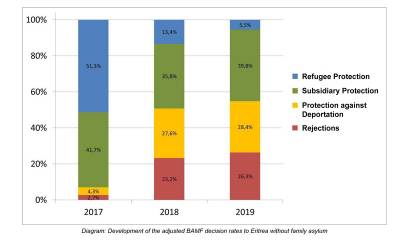

In its statistics, the Federal Office also includes those persons who can obtain protection through family asylum from family members.7 However, if we look exclusively at the recognition practice of all those whose grounds for asylum were examined individually, the massive deterioration is even more marked. As can be seen in the following adjusted chart, the rate of refugee recognition in the substantive examinations for the year 2018 is only 13.4%. In 2019, it has fallen even further to only 5.5%.

This drastic change in decision-making practices in recent years could only be reasonably explained if there had been a profound change in the political situation in Eritrea. However, the situation has hardly changed in the country, which is dictatorially governed by President Isayas Afewerki and the single party People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ). People are still arbitrarily detained and tortured indefinitely without trial, the constitution is still not implemented and there is no independent judiciary. The so-called national service for men and women is a compulsory military service for an indefinite period and is not even remotely remunerated sufficiently to secure a livelihood. Despite the peace agreement, those in power have so far taken no demonstrable steps to demobilise the National Service or to limit its duration.8 Furthermore, leaving the country without a permit is a criminal offence, which is punishable by imprisonment, torture and other ill-treatment.

Therefore, PRO ASYL and Connection e.V. cannot conclude that the changed situation in Eritrea is in any way a reason for the increasingly restrictive decision-making practice for Eritrean refugees. Rather, it seems to be based on the political will to significantly reduce the recognition rates in Germany.9 The lawyer Simone Rapp states that the situation report of the Federal Foreign Office - which is an important basis for the decisions of the Federal Office and the courts - suggests that the high level of flight from Eritrea is primarily for economic reasons.10 With this view, the Federal Foreign Office [Auswärtiges Amt] increasingly distances its position from the assessments of the United Nations and non-governmental organisations, which overwhelmingly recognise the national service as one of the main causes of flight. Unimpressed by the statement of the UN Special Rapporteur, who raised concern about the increasingly rejective nature of the decisions towards Eritrean asylum seekers,11 the Foreign Office’s situation report seems to aim at negatively influencing the decision-making practice of the Federal Office and the courts.12 Figures show that this approach is successful. For the few refugees who make it from Eritrea to Germany, it is becoming increasingly difficult to obtain effective protection from the persecuting state, regardless of the situation in their country of origin.

However, the dictatorship in Eritrea must not be played down and must be condemned as an unjust regime. The National Service forces loyalty and obedience to the regime. Those who flee from there, evade it and thereby expose themselves to arbitrary punishment, need and deserve protection.

Draft evasion, conscientious objection and desertion

Although the escape from the Eritrean national service involves the threat of arbitrary detention without due process of law and often torture, the Federal Office and many courts believe that this sanction, which is linked to a withdrawal from military service, is not sufficient for refugee recognition - unlike a few years ago. The threat of punishment is significant under refugee law if it is linked to a relevant characteristic such as political conviction.13 It is assumed that the severity of the punishment indicates whether an opposing political opinion is underlying (Politmalus [Politmalus are (criminal) sanctions that are discriminatory, disproportionate, excessive or arbitrary]). Since there is hardly any reliable information available, the decision makers try to put themselves in the position of the persecutor and draw the conclusion that the Eritrean state cannot assume, "realistically", that so many persons are critical of the regime and therefore punishes deserters, regardless of their political conviction, solely on the basis of the non-fulfilment of their civic duty.

With this conclusion, the decision makers come to the determination that this is only a purely criminal prosecution, as would be the case in other countries in cases of withdrawal from military service and desertion. Therefore, they conclude, this is not a political persecution. This is to be firmly contradicted. A punishment that serves to maintain a dictatorial structure of rule is political per se, because the punishment is intended to safeguard the political goals of a totalitarian state.

In addition, in the case of Eritrea, a state prosecution is taking place without any legal basis. There is no legal system, no legal representation, no prosecution, no court, no orderly procedure. Such an approach is a very effective way of intimidating political opponents and systematically suppressing opposition. Anyone who can empathize with the motivation of the persecutors in the manner described will nolens volens be co-responsible.

Eritreans who go into hiding or flee before they receive a draft order for the National Service must have to take additional steps to justify themselves as asylum seekers, because in this case, according to the Federal Office and some courts, the penalty in Eritrea is lower. However, this implies that Eritreans should wait for the call-up order to go to the national service, which is certain to be issued; this is clearly life threatening. Those who are already in the military are exposed to a much higher risk when fleeing. Also, the assertion of the decision makers that it can be assumed that punishment can be reliably assessed is incorrect. In 2017, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees assured PRO ASYL of their understanding that "the actions of the Eritrean security forces are characterised by arbitrariness (e.g. duration of detention from a few weeks to several months, accommodation in metal containers, etc.) and can go far beyond the fundamentally legitimate punishment of desertion".14 This insight now seems to have changed without any factual basis.

In a system where the governance is based solely on arbitrariness and in which the decision-making authority lies solely with the military superiors, any practice based on the rule of law cannot be assumed.

Arbitrariness as an effective system of rule

In the case of asylum seekers who have fled before their persecution has fully begun, the Federal Office examines whether there is a considerable likelihood of political persecution or inhuman treatment. Since not all persons are threatened with persecution or inhuman treatment, the burden of proof is imposed on the persons seeking protection: They must explain why they, of all people, are threatened with particularly severe punishment.

Those who cannot sufficiently justify this may not even be granted subsidiary protection, but may be rejected altogether. In this downward spiral, the Federal Office often quotes a ruling of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).15 This ruling also requires that the person concerned must demonstrate in concrete terms that he or she is actually at risk of inhuman treatment. However, in this case the Court assumed that the person concerned had not left the country illegally, which is not the case for the majority of refugees from Eritrea. However, the Court then dealt with the question of what threatens conscripts who have left the country illegally and stated: "that the harsh punishment of deserters and persons of conscript age is still widespread "16. However, this is deliberately ignored by the Federal Office. With reference to this judgement, refugees who left the country illegally are unlawfully denied protection.17

Irrespective of these particular cases, it is problematic in any case to impose such a high burden of proof on asylum seekers in the first place. This is first of all underwritten by the principle that "a foreigner - insofar as he/she invokes circumstances in his/her country of origin - cannot be required to provide full proof, but it is sufficient to provide credibility”,18 according to the Federal Office itself.

Moreover, in the case of Eritrea, the fact that punishment is not based on a functioning legal apparatus with perhaps some lax or inconsistent prosecution, but on a system of arbitrariness, is ignored. Requiring those seeking protection to give reasons on why they are threatened with harsher punishment than others is completely mistaken in the context of the system. The very fact that it can affect anyone and everyone is the core of an arbitrary system. This system is extremely useful to the regime: a climate of fear is maintained at a fairly low cost. Arbitrariness is an instrument of rule that achieves maximum benefit at minimum cost. It can affect any person at any time - in the case of Eritrea even family members - and no one can hope for an independent judiciary.

Conscientious objection, desertion and draft evasion should be recognized as group persecution

Completely ignored by the Federal Office and many courts is the fact that persons who refuse the Eritrean military service, desert or evade national/military service are perceived by state authorities and the military as individuals who are disloyal to state doctrine because they evade the most important institution for the enforcement of the doctrine, the unlimited conscription.

According to the UNHCR, conscientious objectors are "a particular social group given that they share a belief which is fundamental to their identity and that they may also be perceived as a particular group by society"19.

Furthermore, deserters who leave the service in Eritrea without permission, or those who do not serve in the military, are showing their disloyalty towards a national service, which has an important ideological value as the ’school of the nation’, with this act. The purpose of the national service is to "[t]o create a new generation characterised by love of work, discipline and a willingness to participate and serve in the reconstruction of the nation " and to “[t]o foster national unity among our people by eliminating sub-national feelings.”20 Thus, those who avoid this measure of political education inevitably belong to a certain social group. What the UNHCR continues to say must therefore also apply to Eritrea:

"In some societies, deserters may be considered as a particular social group if the general attitude towards military service is seen as a sign of loyalty to the country and/or because of the different treatment of such persons (e.g. discrimination in access to public service jobs), which leads to their exclusion or distinction as a group. This may also be the case for those who have been drafted into military service".21

In totalitarian states, there can be no legitimate civic duty; German history also teaches us that. State autonomy must not be valued more highly than individual resistance to a totalitarian system. A dictatorship cannot be entitled to a national service. Democratic societies have the obligation to support conscientious objectors of a dictatorial regime in such situations.

Trivialisation of forced labour

The United Nations has repeatedly criticized the national service in Eritrea, which is indefinitely in nature. As recently as March 2019, the UN Commission on Human Rights expressed concern that conscripts are sometimes deployed in private mining and construction companies where they receive little or no pay. The Commission on Human Rights called on Eritrea to "refrain from subjecting persons in military service to activities that may amount to forced labour"22 and the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea in 2016 stated in its Detailed Findings:

“The Commission concludes that Eritrea’s military/national service programmes violate Article 565 of Eritrea’s Transitional Penal Code which criminalises enslavement. They also violate Article 8 of the ICCPR, Article 5 of the ACPHR, and the Slavery Convention of 1926. Aspects of the programmes also violate Articles 9, 10, 12, 17 and 22 of the ICCPR, Articles 8, 12, 15 and 18 of the ACHPR, and the 1930 and 1957 conventions on forced labour. As will be discussed in greater detail below, the Commission has concluded that programmes also constitute the crime against humanity of enslavement."23

In November 2014, three Eritreans accused the Canadian company Nevsun in Vancouver of forced labour under the company’s premises at the Bisha mine in Eritrea. The Supreme Court of British Columbia permitted this lawsuit for crimes against humanity, slavery, forced labour and torture against Nevsun, as a fair trial could not be assumed in Eritrea.24 The case is still pending.

Forced labour and slavery are prohibited under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and are thus also relevant in asylum procedures (most of all when it comes to the question of “prohibitions on deportation” [Abschiebungsverboten]). The most recent report of the European Asylum Support Office (EASO)25 states that the National Service comprises "a military and a civil component":

“Part of the conscripts are assigned to one of the approximately 30 companies owned by the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) or the army, which are active in fields such as agriculture, construction, transport, tourism, or trade.”26

According to the proclamation that introduced the service in 1994, the deployment in the National Service also serves the reconstruction of the nation and the development of the country.27 This characterization, defined by the Eritrean regime itself, is often used to refer to a service oriented towards the common good. In order to underline this, the Federal Office and some courts like to draw on judgement from the German context: The German Karlheinz Schmidt filed a suit with the European Court of Human Rights against the obligation of the municipality of Tettnang to either serve in the fire brigade or to pay a levy of 75 DM.28 The judgement states that only the obligations can only be considered forced labour, within the context of the ECHR, if they do not correspond to the basic idea of the general interest, social solidarity and customary practice. The Federal Office and some administrative courts inclined to equate the Tettnang fire brigade fine of DM 75 with the unlimited national service under the arbitrary rule of military superiors in Eritrea.29

The counter to this is that in a dictatorship, it is not the general public that profits, but only a small group that derives economic benefit from the rule and secures power for itself. The maintenance of political power and private financial interests of a small group do not correspond to the most basic idea of the general interest. This becomes all too clear in the structure described by EASO when it is explained that the national service is to be performed in companies that belong either to the state party or directly to the military.

To emphasize again: the National Service in does not in any way involve voluntary work, even if it is in the non-military sphere. The service conscripts remain under the direction and supervision of the military. Removal from service is considered desertion. There is no possibility for the service conscripts to terminate such forced labour relationships. The National Service also fulfils ideological and educational objectives and is therefore a tool for maintaining political power. In view of this, anyone who presents the National Service as a kind of job creation measure under conditions of poverty is complicit in maintaining the system of forced labour and forced ideological education.

Letter of regret and 2% tax

The dictatorship is also able to exert its influence on Eritreans living in Germany, thanks to the policies of the German authorities. Those who have not been recognised as refugees and have only been granted subsidiary protection or protection against deportation are requested to obtain their passports from the Eritrean embassy. Many foreigners authorities consider this to be reasonable, although it means that the persons concerned must again submit completely to the requirements of the Eritrean regime.

Services such as the issuing of a passport are only provided by the Eritrean mission abroad if a letter of repentance is signed beforehand,30 in which the person signing the letter states: “I regret having committed an offence by failing to fulfill my national obligation and that I am willing to accept the appropriate measures when decided."31 The undersigned thereby surrenders to imprisonment and punishment without any legal basis. It is a carte blanche to exercise arbitrary rule, free from any and all legal requirements. The Federal Government’s answer to this issue is succinct: "The making of declarations before the authorities of the state of origin in the context of obtaining a passport does not in itself constitute unreasonableness."32

In addition to signing the letter of repentance, Eritreans are required by the regime to pay a tax of 2% of their income from when they left Eritrea until now. The German government is unimpressed by the fact that reports of blackmailing associated with tax collection in the Netherlands have led to the deportation of an Eritrean diplomat.33 Scientific findings that the tax must either be paid by relatives in Eritrea or is collected in Germany by government-related agencies and groups for the embassy are ignored by the German government, as are reports of associated repression.34

Despite all this, those who do not have refugee status are still requested to obtain a passport from the Eritrean mission abroad. Thus the downward spiral in the recognition of Eritrean refugees considerably strengthens the influence of the Eritrean dictatorship in Germany. The Eritrean regime’s aim of suppressing all opposition through deterrence and fear is thus strengthened by the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, by courts and authorities.35

Claims of PRO ASYL and Connection e.V.

We call on the German government to demand unequivocal respect for human rights from the Eritrean government. This includes the release of all conscientious objectors and political prisoners. It also includes effective and sustainable measures to guarantee democracy and human rights;

We call on German authorities and courts to grant Eritrean refugees the necessary protection. In view of the fact that conscripts, both men and women, evade or refuse to perform national service under a totalitarian regime, which serves the purpose of political education, the persecution of military service withdrawal and desertion must be regarded as political persecution;

We call on German authorities and courts to consider persons from Eritrea who refuse military service, desert or evade national/military service, according to the UNHCR definition, as a social group in the meaning of the Geneva Convention. Their persecution must therefore lead to recognition as refugees;

We call on German authorities and courts to stop the practice of demanding cooperation of Eritrean refugees with the Eritrean regime from which they fled. In view of the fact that the Eritrean authorities are demanding a carte blanche to prosecute and require payment of a 2% tax, refugees who have been granted subsidiary protection or protection against deportation must not be forced to seek passports from their country of origin.

We also call on the German Federal Government to support organisations and initiatives of the Eritrean diaspora that are committed in various ways to the implementation of human rights and democracy in Eritrea. This would also send a clear political signal to the Eritrean government.

Footnotes

1 Amnesty International (2019): Eritrea – Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee, January 2019, AFR 64/9778/2019.

2 UN Human Rights Committee (2019): Concluding Observations on Eritrea in the absence of its initial report. 3.5.2019, CCPR/C/ERI/CO/1, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2fC%2fERI%2fCO%2f1 (24.10.19).

3 UN Human Rights Council, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Eritrea (2019): Situation of human rights in Eritrea, May 16, 2019, A/HRC/41/53, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G19/140/37/PDF/G1914037.pdf (30.10.19).

4 Human Rights Watch (2019): „They Are Making Us into Slaves, Not Educating Us“, August 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/08/08/they-are-making-us-slaves-not-educating-us/how-indefinite-conscription-restricts (11.11.2019).

5 BAMF (2016): Das Bundesamt in Zahlen 2015, https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Publikationen/Broschueren/bundesamt-in-zahlen-2015.pdf (30.10.19), p. 50. This and the following are the adjusted protection rates, in which only the substantive decisions of the Federal Office were included.

6 BAMF (2019): Asylgeschäftsstatistik 1-12/18, http://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Downloads/Infothek/Statistik/Asyl/hkl-antrags-entscheidungs-bestandsstatistikl-kumuliert-2018.html (31.10.19).

7 These are both children born in Germany of recognised refugees and subsidiarity-protected persons and their spouses, children or parents (if at least refugees) who came to Germany via family reunification. The requirements for family asylum are regulated in §26 AsylG.

8 UN Human Rights Council, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Eritrea (2019); Human Rights Watch (2019): World Report 2019 – Eritrea, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/eritrea_2019.pdf (30.10.19).

9 This is also evident in other European countries, as a comparative analysis of the tightening of Swiss refugee assistance shows. See also: SFH/OSAR (2018): Analysis of the Swiss hardening of practice with regard to applicants from Eritrea. Research of the legal department, https://www.fluechtlingshilfe.ch/assets/news/eritrea/181213-recherche-osar-erythree.pdf (04.11.19).

10 Rapp, Simone (2019): No refugee protection in case of withdrawal from the Eritrean National Service?, in: Asylmagazin 8-9/2019, p. 268-275.

11 UN Human Rights Council, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Eritrea (2019), par. 73.

12 Rapp (2019), p. 275.

13 VG Berlin, Jugdment of September 1, 2017 – 28 K 166.17 A; VG Düsseldorf, Jugdment of March 23, 2017 – 6 K 7338/16.A; VG Halle, Jugdment of October 23, 2018 – 4 A 228/17 HAL; BAMF-Bescheid Außenstelle Büdingen 2019; BAMF-Bescheid Außenstelle Leipzig 2019; BAMF-Bescheid Außenstelle Gießen 2019. However, some court assume in general that there is always a link to political conviction: VG Cottbus, Jugdment of April 12, 2019 – 6K652/16.A; VG Magdeburg, Jugdment of May 15, 2019 – 15 A 3628/15; VG Schwerin Jugdment of January 20, 2017 – 15A 3003/16.

14 Reply letter from the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees to PRO ASYL from January 25, 2017.

15 ECtHR, Judgement from 20.06.2017, M.O. v. Switzerland, 41282/16.

16 loc. cit., par. 72

17 BAMF-Bescheid Außenstelle Büdingen 2019; BAMF-Bescheid Außenstelle Deggendorf 2019; BAMF-Bescheid Außenstelle Gießen 2019; BAMF-Bescheid Außenstelle Trier 2019.

18 Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge: DA-Asyl, April 25, 2017, https://www.proasyl.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/DA-Asyl-April-2017.pdf (11.11.2019).

19 UNHCR (2014): Guidelines on International Protection No. 10: Claims to Refugee Status related to Military Service within the context of Article 1A (2) of the 1951 Convention and/or the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, November 2014, https://www.unhcr.org/529efd2e9.html (29.10.19), par. 58.

20 European Asylum Support Office (EASO): Eritrea – National service, exit, and return. September 2019, p. 24.

21 UNHCR (2014): Guidelines on International Protection No. 10, par. 58.

22 UN Commission on Human Rights (2019), paragraph 38

23 UN Human Rights Council (2016): Detailed findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in Eritrea, June 8, 2016, A/HRC/32/CRP.1, www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/CoIEritrea/A_HRC_32_CRP.1_read-only.pdf (01.12.19)

24 See Business and Human Rights Resource Centre: Nevsun lawsuit, www.business-humanrights.org/en/nevsun-lawsuit-re-bisha-mine-eritrea (02.12.19).

25 EASO (2019), p. 24. The European Asylum Support Office (EASO) is a Community agency of the European Union responsible for supporting cooperation between EU Member States in the field of asylum.

26 ibid.

27 See ibid.

28 ECtHR, Decision of July 18, 1994 - Karlheinz Schmidt v. Germany, 13580/88. A ruling of the Constitutional Court on military service in Germany is also frequently quoted in this connection: BVerwG, decision of June 26, 2006 – 6 B 9.06.

29 BAMF-Bescheid Außenstelle Trier 2019; BAMF-Bescheid Außenstelle Bamberg 2019; VG Potsdam, Jugdement of February 17, 2016 – VG 6 K 1995/15.A; VG Schleswig, Jugdement of October 22, 2018, 3 A 365/17.

30 EASO (2019), p. 56; See also: SFH (2017): Quick search of the SFH country analysis of 1 June 2017 on Eritrea: issuing passports in Khartoum, https://www.fluechtlingshilfe.ch/assets/herkunftslaender/afrika/eritrea/170601-eri-khartoum-pass.pdf (29.10.19).

31 Text of the letter of repentance in Tigrinya and English see: DSP-groep/Tilburg School of Humanities (2017): The 2% Tax for Eritreans in the diaspora – Appendices, Juni 2017, https://www.dsp-groep.eu/wp-content/uploads//The-2-Tax-for-Eritreans-in-the-diaspora-Appendices.pdf (29.10.19), p. 24f. Translation: AK.

32 Deutscher Bundestag (2018): Drs. 19/2075, Answer of the Federal Government to the minor question of the Members Ulla Jelpke, Dr. André Hahn, Gökay Akbulut, other Members and the parliamentary group DIE LINKE, http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/19/020/1902075.pdf (07.11.19), Answers question 12.

33 Answer given by the State Secretary to the question put by Mr Schreiber on 05.01.2018, https://dipbt.bundestag.de/doc/btd/19/003/1900370.pdf (21.11.19)

34 For the collection practice also in Germany see: DSP-groep/Tilburg School of Humanities (2017): The 2% Tax for Eritreans in the Diaspora, June 2017, https://www.dsp-groep.eu/wp-content/uploads//The-2-Tax-for-Eritreans-in-the-diaspora_30-august-1.pdf (29.10.19).

35 See also: Amnesty International (2019): Repression without Borders, June 2019, https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/AFR6405422019ENGLISH.PDF (29.10.19).

Statement by PRO ASYL and Connection e.V. on the occasion of the hearing „Conscientious Objection.on the Run - the Human Rights Situation in Eritrea and Germany“, December 9, 2019 in the Bundestag in Berlin. The table and figures from the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees were updated on February 27, 2020.

Keywords: ⇒ Asylum ⇒ CO and Asylum ⇒ Connection e.V. - About Us ⇒ Conscientious Objection ⇒ Eritrea ⇒ Germany ⇒ Human Rights